| Citation: |

Hengbin Ding, Xiaoshi Li, Tianhang Li, Xiaoyong Zhao, He Tian. Controllable thermal rectification design for buildings based on phase change composites[J]. Journal of Semiconductors, 2024, 45(2): 022301. doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/45/2/022301

****

H B Ding, X S Li, T H Li, X Y Zhao, H Tian. Controllable thermal rectification design for buildings based on phase change composites[J]. J. Semicond, 2024, 45(2): 022301. doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/45/2/022301

|

Controllable thermal rectification design for buildings based on phase change composites

DOI: 10.1088/1674-4926/45/2/022301

More Information

-

Abstract

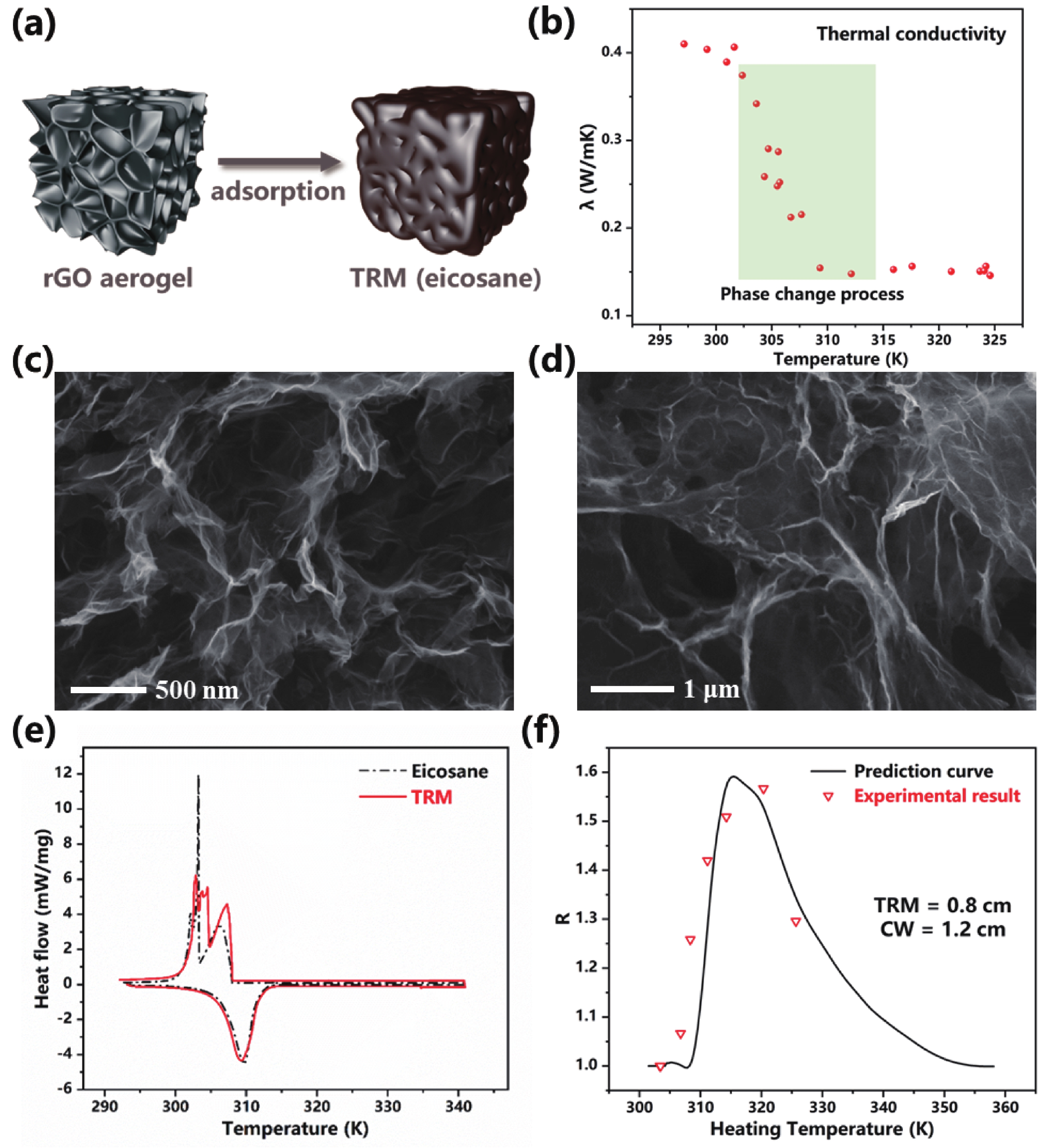

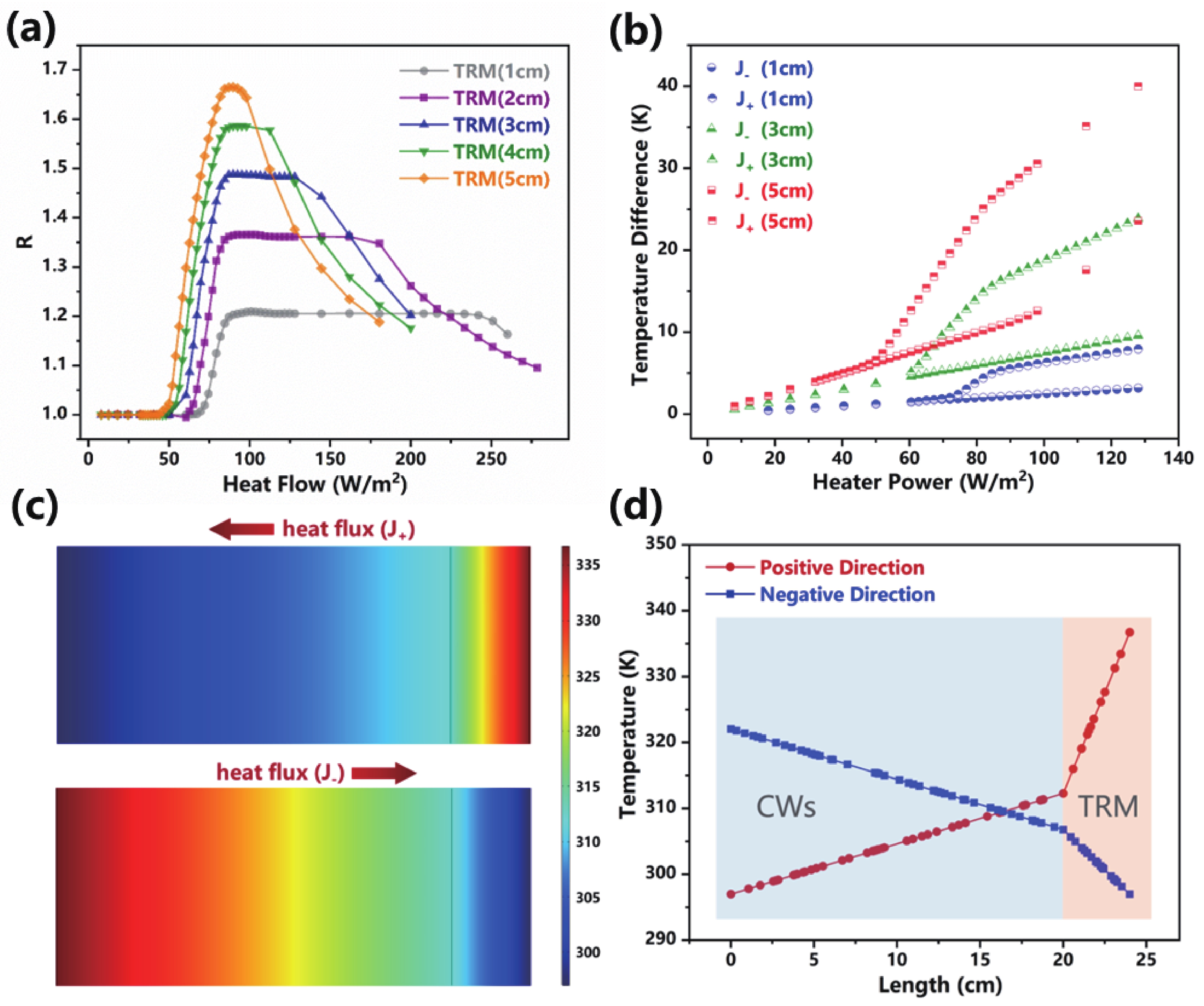

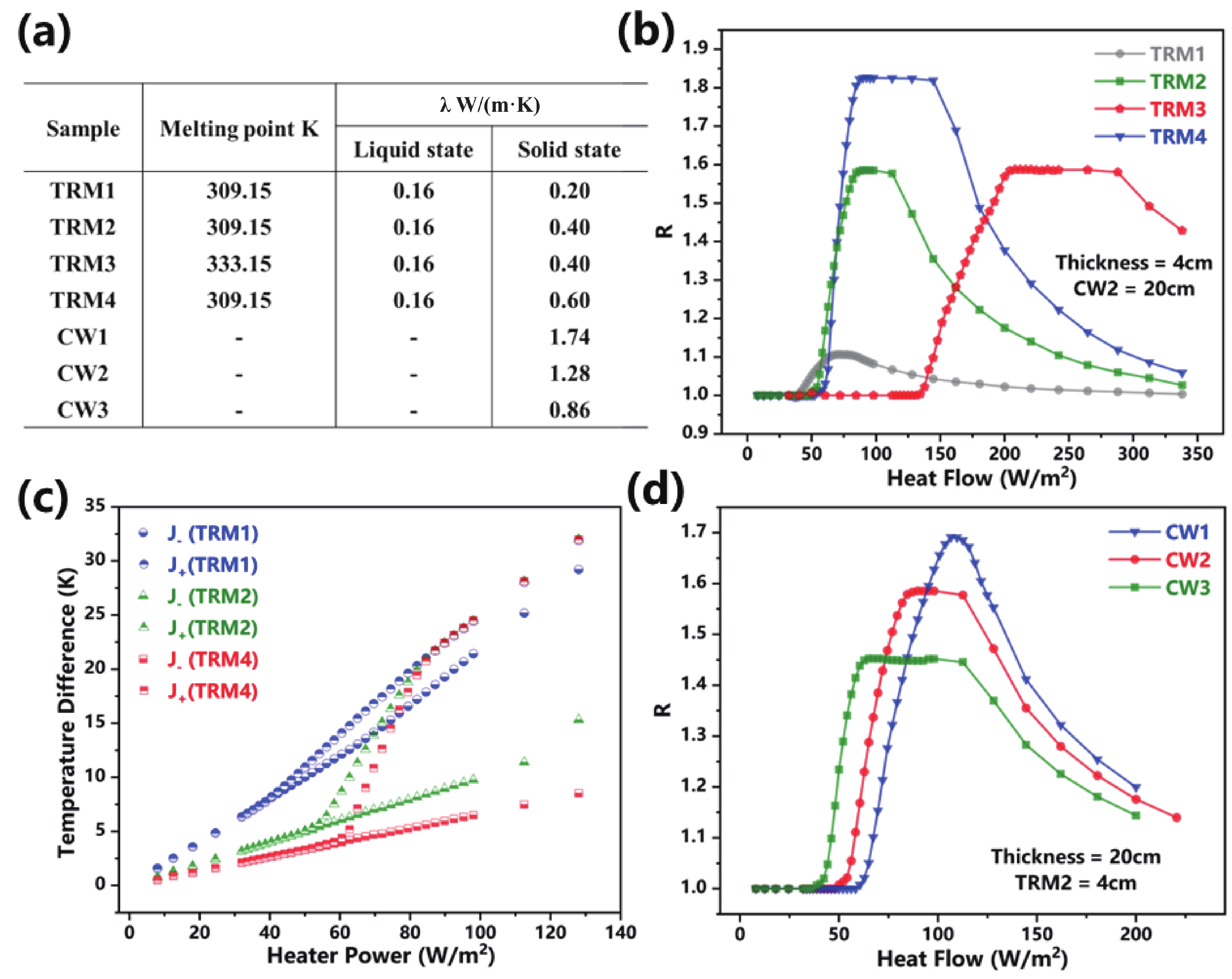

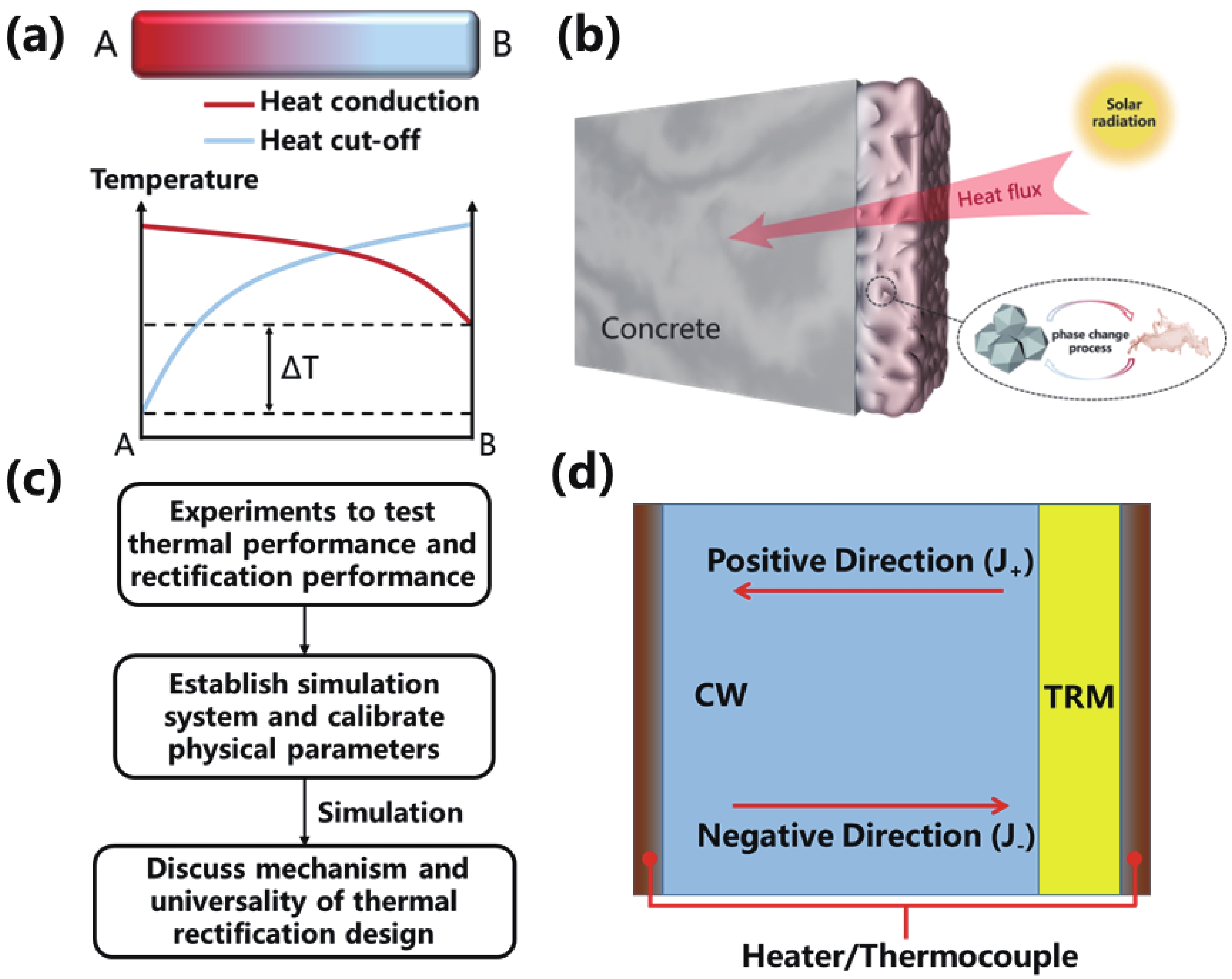

Phase-change material (PCM) is widely used in thermal management due to their unique thermal behavior. However, related research in thermal rectifier is mainly focused on exploring the principles at the fundamental device level, which results in a gap to real applications. Here, we propose a controllable thermal rectification design towards building applications through the direct adhesion of composite thermal rectification material (TRM) based on PCM and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) aerogel to ordinary concrete walls (CWs). The design is evaluated in detail by combining experiments and finite element analysis. It is found that, TRM can regulate the temperature difference on both sides of the TRM/CWs system by thermal rectification. The difference in two directions reaches to 13.8 K at the heat flow of 80 W/m2. In addition, the larger the change of thermal conductivity before and after phase change of TRM is, the more effective it is for regulating temperature difference in two directions. The stated technology has a wide range of applications for the thermal energy control in buildings with specific temperature requirements. -

References

[1] Zhen M, Zou W H, Zheng R, et al. Urban outdoor thermal environment and adaptive thermal comfort during the summer. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 2022, 29, 77864 doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-21162-5[2] Ulutas A, Balo F, Topal A. Identifying the most efficient natural fibre for common commercial building insulation materials with an integrated PSI, MEREC, LOPCOW and MCRAT model. Polymers, 2023, 15, 1500 doi: 10.3390/polym15061500[3] Henry A, Prasher R, Majumdar A. Five thermal energy grand challenges for decarbonization. Nat Energy, 2020, 5, 635 doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-0675-9[4] Li Y, Li W, Han T C, et al. Transforming heat transfer with thermal metamaterials and devices. Nat Rev Mater, 2021, 6, 488 doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00283-2[5] Chang C W, Okawa D, Majumdar A, et al. Solid-state thermal rectifier. Science, 2006, 314, 1121 doi: 10.1126/science.1132898[6] Wang H D, Hu S Q, Takahashi K, et al. Experimental study of thermal rectification in suspended monolayer graphene. Nat Commun, 2017, 8, 15843 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15843[7] Yousefzadi Nobakht A, Ashraf Gandomi Y, Wang J Q, et al. Thermal rectification via asymmetric structural defects in graphene. Carbon, 2018, 132, 565 doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2018.02.087[8] Yang H Y, Tang Y Q, Liu Y, et al. Thermal conductivity of graphene nanoribbons with defects and nitrogen doping. React Funct Polym, 2014, 79, 29 doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2014.03.006[9] Zhang Y F, Lv Q A, Wang H D, et al. Simultaneous electrical and thermal rectification in a monolayer lateral heterojunction. Science, 2022, 378, 169 doi: 10.1126/science.abq0883[10] Zhong W R, Huang W H, Deng X R, et al. Thermal rectification in thickness-asymmetric graphene nanoribbons. Appl Phys Lett, 2011, 99, 193104 doi: 10.1063/1.3659474[11] Liu H X, Wang H D, Zhang X. A brief review on the recent experimental advances in thermal rectification at the nanoscale. Appl Sci, 2019, 9, 344 doi: 10.3390/app9020344[12] Swoboda T, Klinar K, Yalamarthy A S, et al. Thermal control devices: Solid-state thermal control devices. Adv Elect Materials, 2021, 7 doi: 10.1002/aelm.202170008[13] Dames C. Solid-state thermal rectification with existing bulk materials. J Heat Transf, 2009, 131, 1 doi: 10.1115/1.3089552[14] Zhao J N, Wei D, Gao A Q, et al. Thermal rectification enhancement of bi-segment thermal rectifier based on stress induced interface thermal contact resistance. Appl Therm Eng, 2020, 176, 115410 doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115410[15] Tian H, Xie D, Yang Y, et al. A novel solid-state thermal rectifier based on reduced graphene oxide. Sci Rep, 2012, 2, 523 doi: 10.1038/srep00523[16] Aftab W, Huang X Y, Wu W H, et al. Nanoconfined phase change materials for thermal energy applications. Energy Environ Sci, 2018, 11, 1392 doi: 10.1039/C7EE03587J[17] Chen R J, Cui Y L, Tian H, et al. Controllable thermal rectification realized in binary phase change composites. Sci Rep, 2015, 5, 8884 doi: 10.1038/srep08884[18] Chen L J, Zou R Q, Xia W, et al. Electro- and photodriven phase change composites based on wax-infiltrated carbon nanotube sponges. ACS Nano, 2012, 6, 10884 doi: 10.1021/nn304310n -

Proportional views

Hengbin Ding got his bachelor’s degree in 2023 from Beijing University of Technology. Now he is a master student at Tsinghua University under the supervision of Prof. He Tian. His current research focuses on sensors and transistors based on two-dimensional materials.

Hengbin Ding got his bachelor’s degree in 2023 from Beijing University of Technology. Now he is a master student at Tsinghua University under the supervision of Prof. He Tian. His current research focuses on sensors and transistors based on two-dimensional materials. He Tian received the Ph.D. degree from the Institute of Microelectronics, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, in 2015. He is currently an Tenured Associate Professor with Tsinghua University. He has co-authored over 200 papers and more than 10 000 citations. His current research interests include various 2D material-based novel nanodevices.

He Tian received the Ph.D. degree from the Institute of Microelectronics, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, in 2015. He is currently an Tenured Associate Professor with Tsinghua University. He has co-authored over 200 papers and more than 10 000 citations. His current research interests include various 2D material-based novel nanodevices.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: