| Citation: |

Ting Lu, Zhuojun Duan, Ling Zhang, Yuanyuan Jin, Huimin Li, Song Liu. Molecular sieves assisted chemical vapor deposition preparation of high-κ dielectric m-ZrO2 nanosheets[J]. Journal of Semiconductors, 2025, 46(4): 042703. doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090034

****

T Lu, Z J Duan, L Zhang, Y Y Jin, H M Li, and S Liu, Molecular sieves assisted chemical vapor deposition preparation of high-κ dielectric m-ZrO2 nanosheets[J]. J. Semicond., 2025, 46(4), 042703 doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090034

|

Molecular sieves assisted chemical vapor deposition preparation of high-κ dielectric m-ZrO2 nanosheets

DOI: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090034

CSTR: 32376.14.1674-4926.24090034

More Information-

Abstract

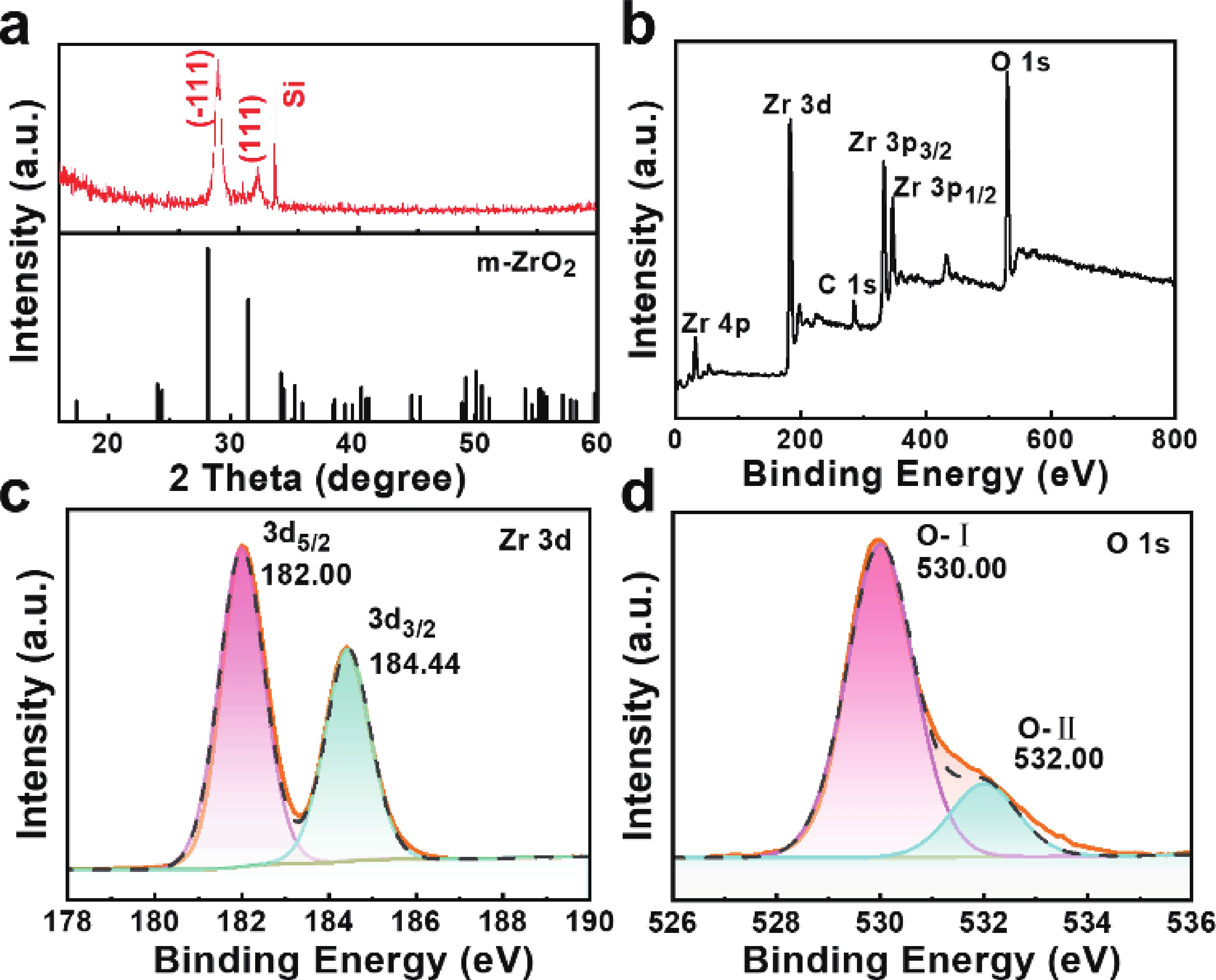

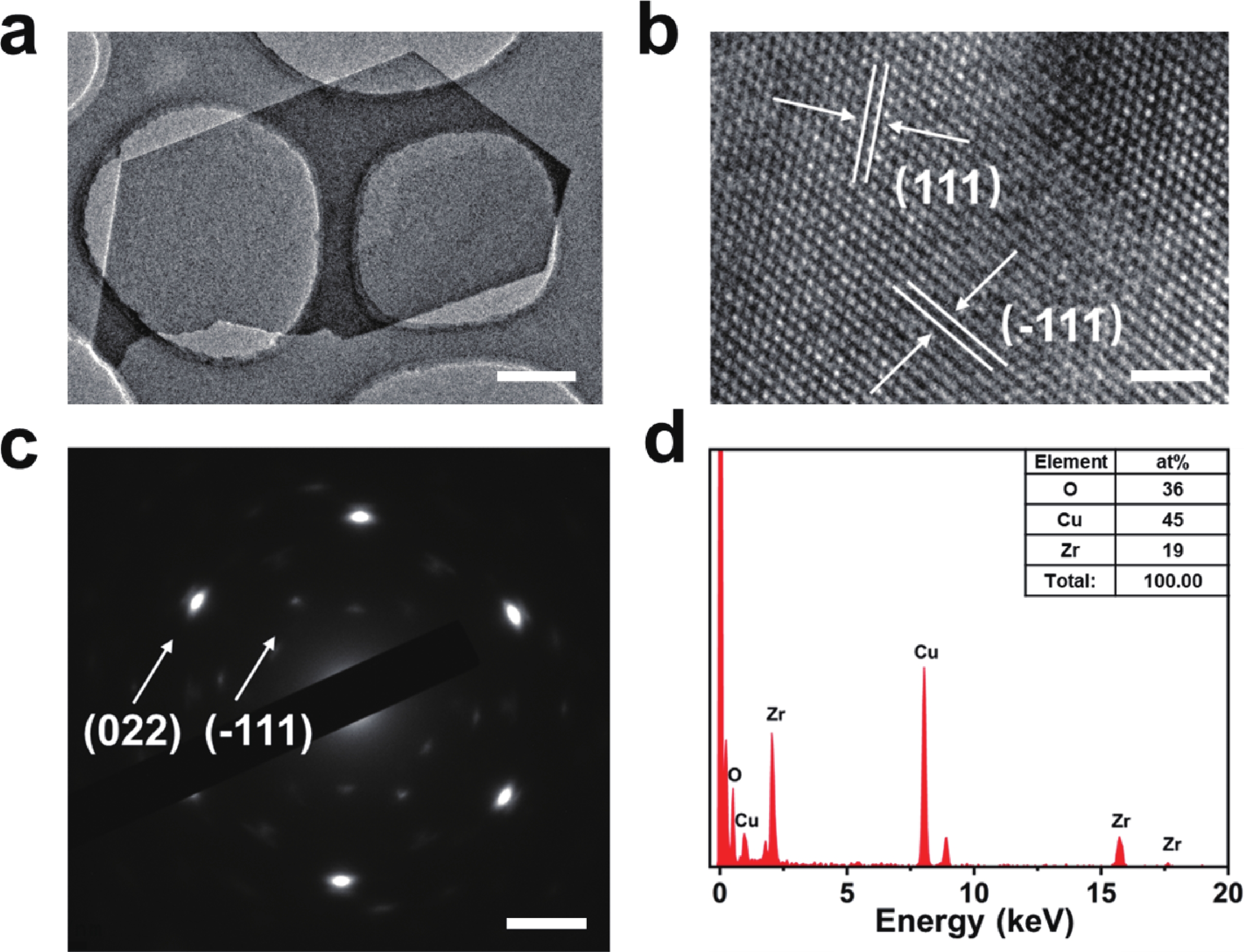

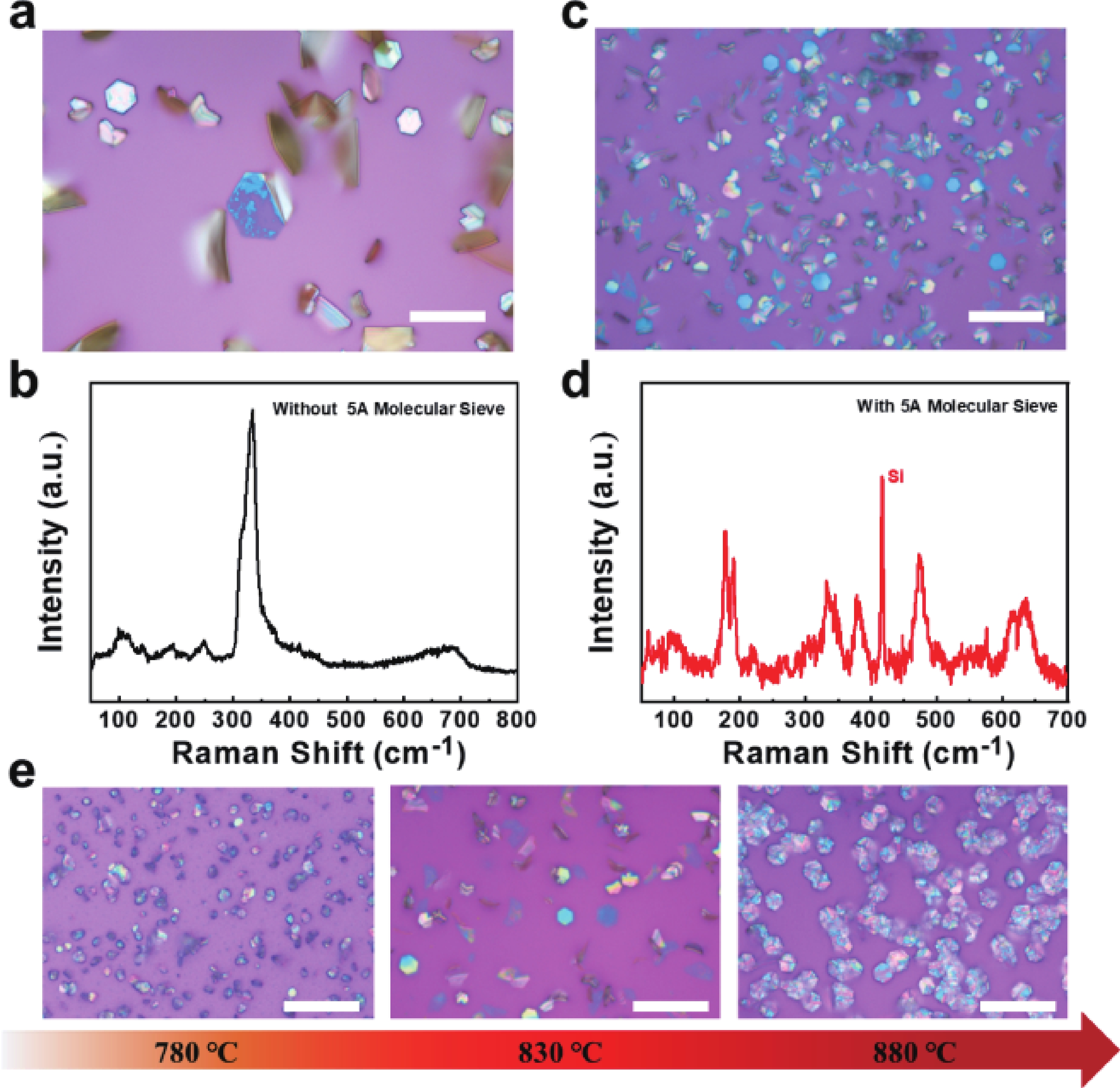

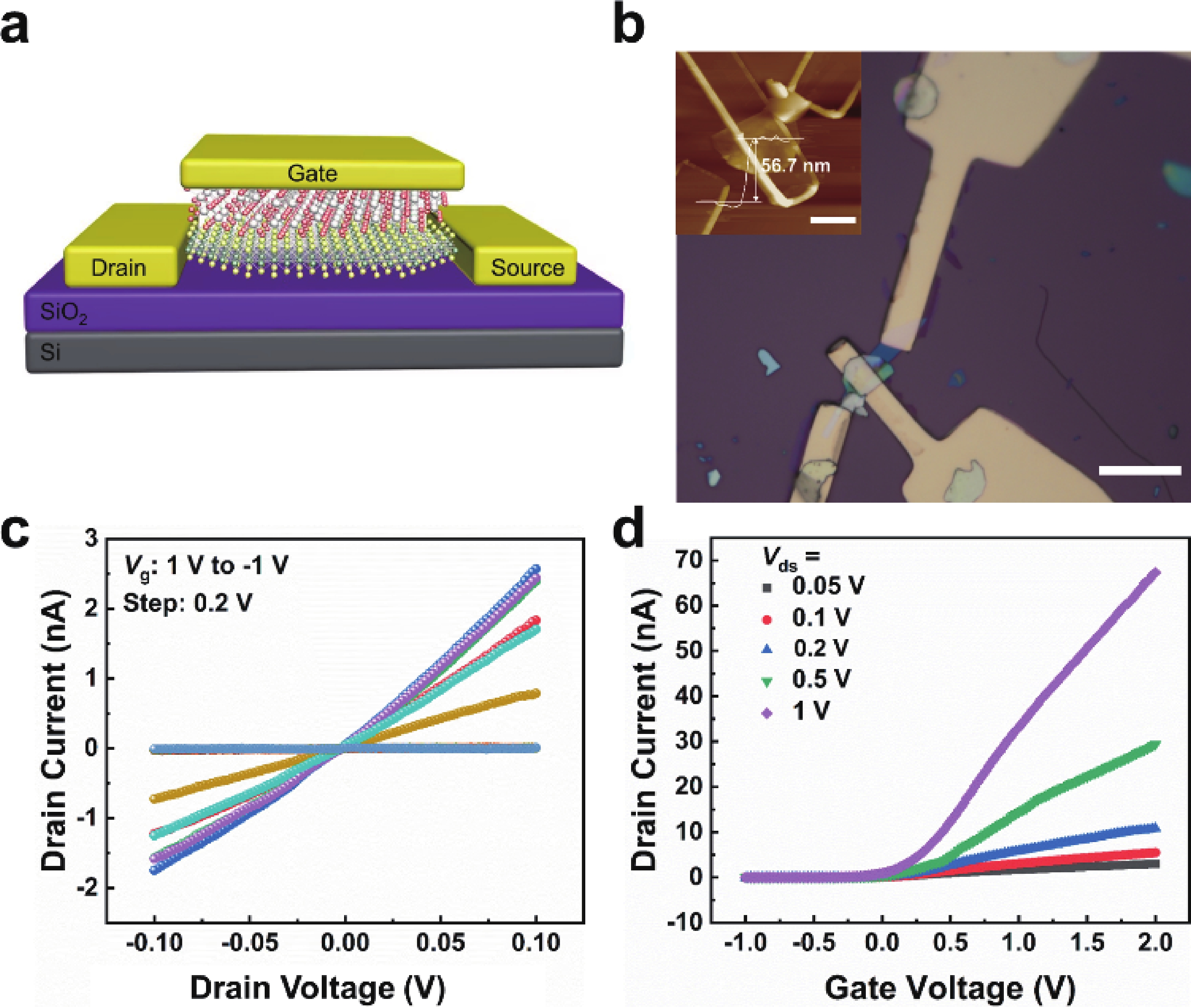

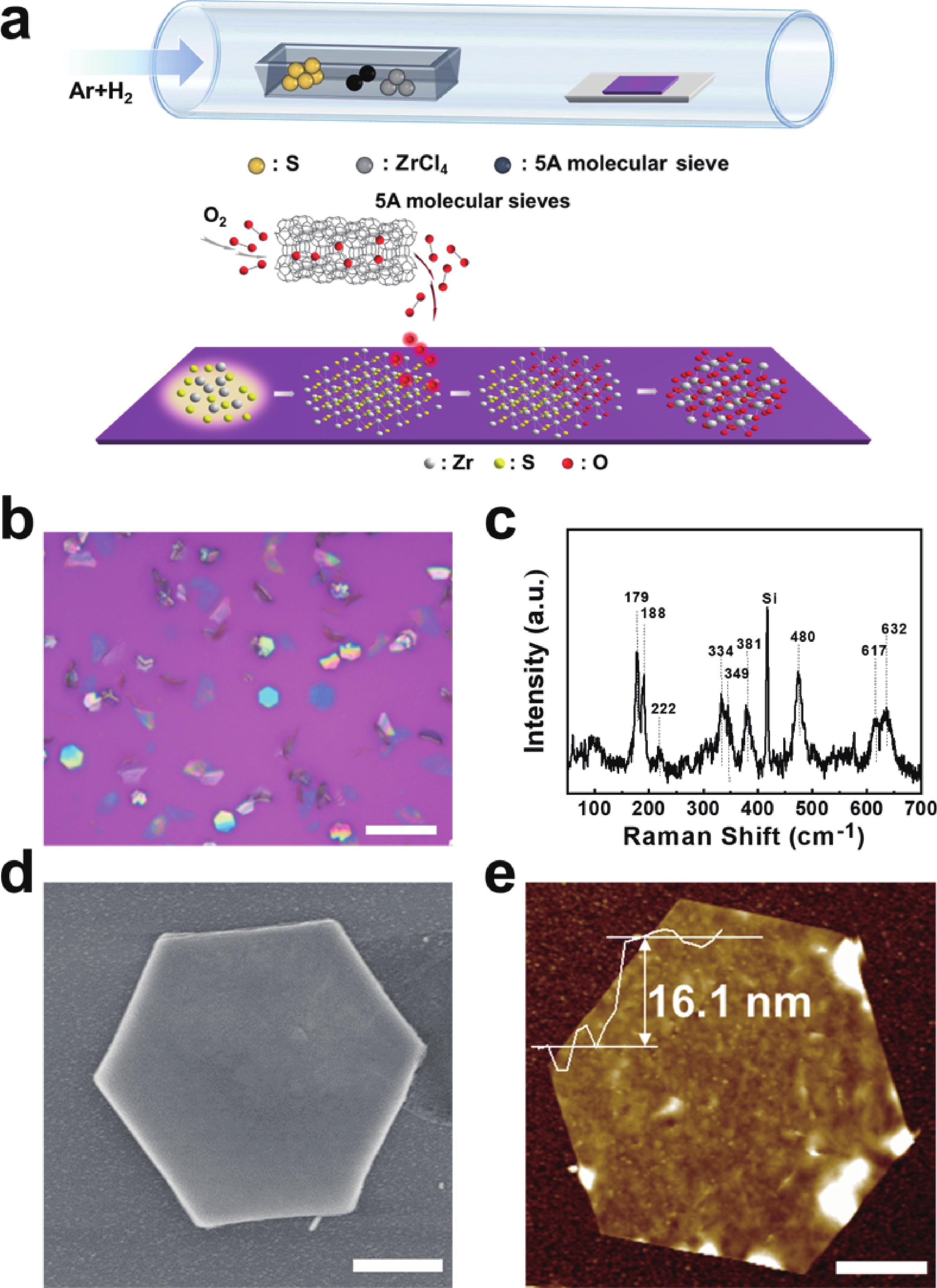

In order to address challenges posed by the reduction in transistor size, researchers are concentrating on two-dimensional (2D) materials with high dielectric constants and large band gaps. Monoclinic ZrO2 (m-ZrO2) has emerged as a promising gate dielectric material due to its suitable dielectric constant, wide band gap, ideal valence-band offset, and good thermodynamic stability. However, current deposition methods face compatibility issues with 2D semiconductors, highlighting the need for high-quality dielectrics and interfaces. Here, high-quality 2D m-ZrO2 single crystals are successfully prepared using a one-step chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method, aided by 5A molecular sieves for oxygen supply. The prepared ZrO2 is utilized as a gate dielectric in the construction of MoS2 field-effect transistors (FETs) to investigate its electrical property. The FETs exhibit a high carrier mobility of up to 5.50 cm2·V−1·s−1, and a current switching ratio (Ion/off) of approximately 104, which aligns with the current standards of logic circuits, indicating that ZrO2 has application value as a gate dielectric. The successful one-step preparation of single-crystal ZrO2 paves the way for the utilization of high-κ gate dielectrics and creates favorable conditions for the development of high-performance semiconductor devices, offering new possibilities for transistor miniaturization. -

References

[1] Li M Y, Su S K, Wong H P, et al. How 2D semiconductors could extend Moore’s law. Nature, 2019, 567, 169 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00793-8[2] Arden W. Future semiconductor material requirements and innovations as projected in the ITRS 2005 roadmap. Mater Sci Eng B, 2006, 134, 104 doi: 10.1016/j.mseb.2006.07.004[3] Liu Y, Duan X D, Shin H J, et al. Promises and prospects of two-dimensional transistors. Nature, 2021, 591, 43 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03339-z[4] Buchanan D A. Scaling the gate dielectric: Materials, integration, and reliability. IBM J Res Dev, 1999, 43, 245 doi: 10.1147/rd.433.0245[5] Valasa S, Tayal S, Thoutam L R, et al. A critical review on performance, reliability, and fabrication challenges in nanosheet FET for future analog/digital IC applications. Micro Nanostruct, 2022, 170, 207374 doi: 10.1016/j.micrna.2022.207374[6] Chen J X, Xu W T. 2D-materials-based optoelectronic synapses for neuromorphic applications. eScience, 2023, 3, 100178 doi: 10.1016/j.esci.2023.100178[7] Meng Z Y, Qiu Z M, Shi Y X, et al. Micro/nano metal-organic frameworks meet energy chemistry: A review of materials synthesis and applications. eScience, 2023, 3, 100092 doi: 10.1016/j.esci.2023.100092[8] Peimyoo N, Barnes M D, Mehew J D, et al. Laser-writable high-κ dielectric for van der Waals nanoelectronics. Sci Adv, 2019, 5, eaau0906 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau0906[9] Ribes G, Mitard J, Denais M, et al. Review on high-κ dielectrics reliability issues. IEEE Trans Device Mater Reliab, 2005, 5, 5 doi: 10.1109/TDMR.2005.845236[10] Houssa M, Pantisano L, Ragnarsson L Å, et al. Electrical properties of high-κ gate dielectrics: Challenges, current issues, and possible solutions. Mater Sci Eng R Rep, 2006, 51, 37 doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2006.04.001[11] Huang T, Ding J F, Liu Z R, et al. Insight into the underlying competitive mechanism for the shift of the charge neutrality point in a trilayer-graphene field-effect transistor. eScience, 2022, 2, 319 doi: 10.1016/j.esci.2022.03.005[12] Kim H J, Osada M, Ebina Y, et al. Hunting for monolayer oxide nanosheets and their architectures. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 19402 doi: 10.1038/srep19402[13] Shin G H, Lee G B, An E S, et al. High-performance field-effect transistor and logic gates based on GaS-MoS2 van der waals heterostructure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2020, 12, 5106 doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b20077[14] Wen C, Lanza M. Calcium fluoride as high-κ dielectric for 2D electronics. Appl Phys Rev, 2021, 8, 021307 doi: 10.1063/5.0036987[15] Holler B A, Crowley K, Berger M H, et al. 2D semiconductor transistors with van der waals oxide MoO3 as integrated high-κ gate dielectric. Adv Elect Materials, 2020, 6, 2000635 doi: 10.1002/aelm.202000635[16] Chamlagain B, Cui Q S, Paudel S, et al. Thermally oxidized 2D TaS2 as a high-κ gate dielectric for MoS2 field-effect transistors. 2D Mater, 2017, 4, 031002 doi: 10.1088/2053-1583/aa780e[17] Tu T, Zhang Y C, Li T R, et al. Uniform high-κ amorphous native oxide synthesized by oxygen plasma for top-gated transistors. Nano Lett, 2020, 20, 7469 doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02951[18] Mleczko M J, Zhang C F, Lee H R, et al. HfSe2 and ZrSe2: Two-dimensional semiconductors with native high-κ oxides. Sci Adv, 2017, 3, e1700481 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700481[19] Wong Y H, Cheong K Y. ZrO2 thin films on Si substrate. J Mater Sci Mater Electron, 2010, 21, 980 doi: 10.1007/s10854-010-0144-5[20] Jia B B, Zhang B H, Cai Z, et al. Construction of amorphous/crystalline heterointerfaces for enhanced electrochemical processes. eScience, 2023, 3, 100112 doi: 10.1016/j.esci.2023.100112[21] McDonnell S, Brennan B, Azcatl A, et al. HfO2 on MoS2 by atomic layer deposition: Adsorption mechanisms and thickness scalability. ACS Nano, 2013, 7, 10354 doi: 10.1021/nn404775u[22] Zou X M, Wang J L, Chiu C H, et al. Interface engineering for high-performance top-gated MoS2 field-effect transistors. Adv Mater, 2014, 26, 6255 doi: 10.1002/adma.201402008[23] Wang J L, Li S L, Zou X M, et al. Integration of high-κ oxide on MoS2 by using ozone pretreatment for high-performance MoS2 top-gated transistor with thickness-dependent carrier scattering investigation. Small, 2015, 11, 5932 doi: 10.1002/smll.201501260[24] Qiu H, Yu Z H, Zhao T G, et al. Two-dimensional materials for future information technology: Status and prospects. Sci China Inf Sci, 2024, 67, 160400 doi: 10.1007/s11432-024-4033-8[25] Zhao T G, Guo J X, Li T T, et al. Substrate engineering for wafer-scale two-dimensional material growth: Strategies, mechanisms, and perspectives. Chemical Soc Rev, 2023, 52, 1650 doi: 10.1039/D2CS00657J[26] Yamada T, Kubota Y, Makinose Y, et al. Single crystal ZrO2 nanosheets formed by thermal transformation for solid oxide fuel cells and oxygen sensors. ACS Appl Nano Mater, 2019, 2, 6866 doi: 10.1021/acsanm.9b01312[27] Jin Y Y, Sun J, Zhang L, et al. Controllable oxidation of ZrS2 to prepare high-κ, single-crystal m-ZrO2 for 2D electronics. Adv Mater, 2023, 35, e2212079 doi: 10.1002/adma.202212079[28] Li M J, Feng Z C, Xiong G, et al. Phase transformation in the surface region of zirconia detected by UV Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B, 2001, 105, 8107 doi: 10.1021/jp010526l[29] Ding S, Zhao J K, Yu Q. Effect of zirconia polymorph on vapor-phase ketonization of propionic acid. Catalysts, 2019, 9, 768 doi: 10.3390/catal9090768[30] Mañas-Valero S, García-López V, Cantarero A, et al. Raman spectra of ZrS2 and ZrSe2 from bulk to atomically thin layers. Appl Sci, 2016, 6, 264 doi: 10.3390/app6090264 -

Proportional views

Ting Lu received her BS degree from Chongqing Normal University in 2022 and is now a master's candidate at Hunan University under Professor Song Liu. Her research direction is two-dimensional materials and devices.

Ting Lu received her BS degree from Chongqing Normal University in 2022 and is now a master's candidate at Hunan University under Professor Song Liu. Her research direction is two-dimensional materials and devices. Zhuojun Duan received her M.Sc degree of Physics from Xiangtan University in 2021. She is a Ph.D. student of chemistry in Hunan University supervised by Professor Song Liu. Her research mainly focuses on controllable synthesis of two-dimensional materials by CVD method.

Zhuojun Duan received her M.Sc degree of Physics from Xiangtan University in 2021. She is a Ph.D. student of chemistry in Hunan University supervised by Professor Song Liu. Her research mainly focuses on controllable synthesis of two-dimensional materials by CVD method. Song Liu received his BS degree from Nankai University in 2006 and PhD degree at Peking University in 2011. Then he joined the team of Professor Liming Dai at Case Western Reserve University in the United States as a postdoctoral fellow. He joined the National University of Singapore as a research fellow. He joined Hunan University in 2016 as a full professor. His research interests include controlled synthesis of low-dimensional layered materials, application research of functional devices, and flexible wearable sensors.

Song Liu received his BS degree from Nankai University in 2006 and PhD degree at Peking University in 2011. Then he joined the team of Professor Liming Dai at Case Western Reserve University in the United States as a postdoctoral fellow. He joined the National University of Singapore as a research fellow. He joined Hunan University in 2016 as a full professor. His research interests include controlled synthesis of low-dimensional layered materials, application research of functional devices, and flexible wearable sensors.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: