| Citation: |

Miao Cheng, Yifan Xie, Jinyao Wang, Qingqing Jin, Yue Tian, Changrui Liu, Jingyun Chu, Mengmeng Li, Ling Li. Neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses based on organic electrochemical transistors for future biomimic and bioinspired neuromorphic systems[J]. Journal of Semiconductors, 2025, 46(1): 011604. doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090013

****

M Cheng, Y F Xie, J Y Wang, Q Q Jin, Y Tian, C R Liu, J Y Chu, M M Li, and L Li, Neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses based on organic electrochemical transistors for future biomimic and bioinspired neuromorphic systems[J]. J. Semicond., 2025, 46(1), 011604 doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090013

|

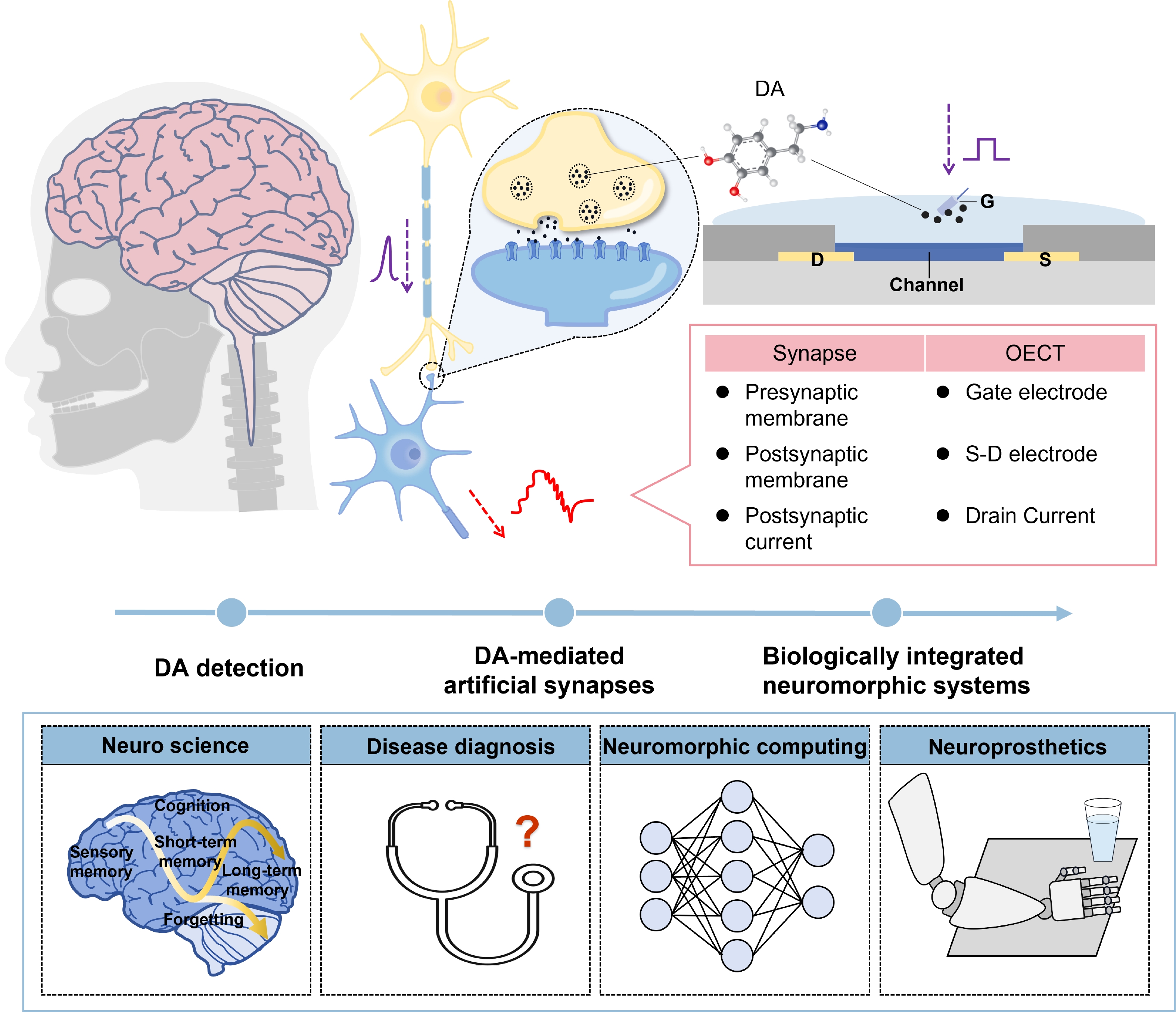

Neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses based on organic electrochemical transistors for future biomimic and bioinspired neuromorphic systems

DOI: 10.1088/1674-4926/24090013

CSTR: 32376.14.1674-4926.24090013

More Information-

Abstract

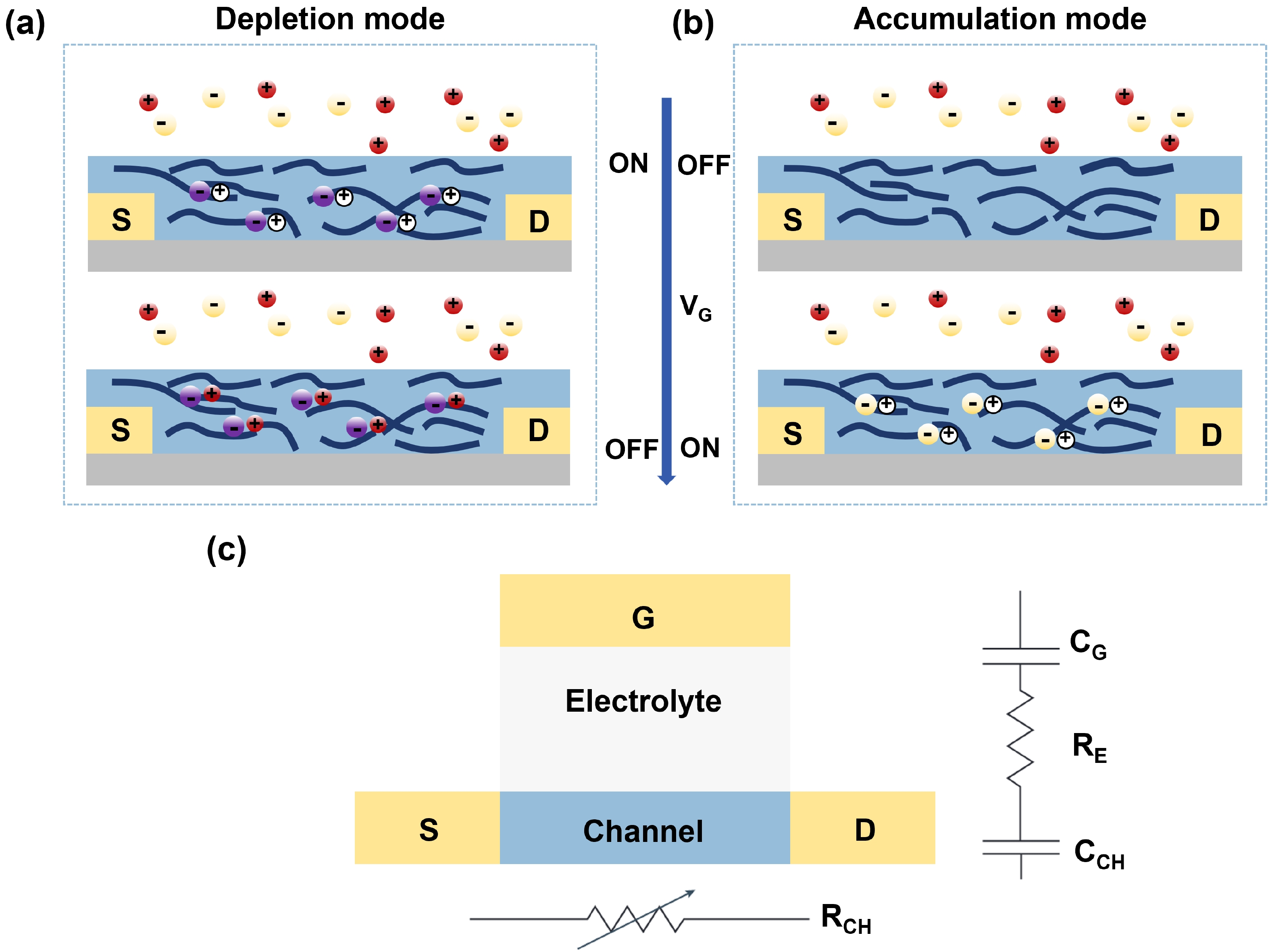

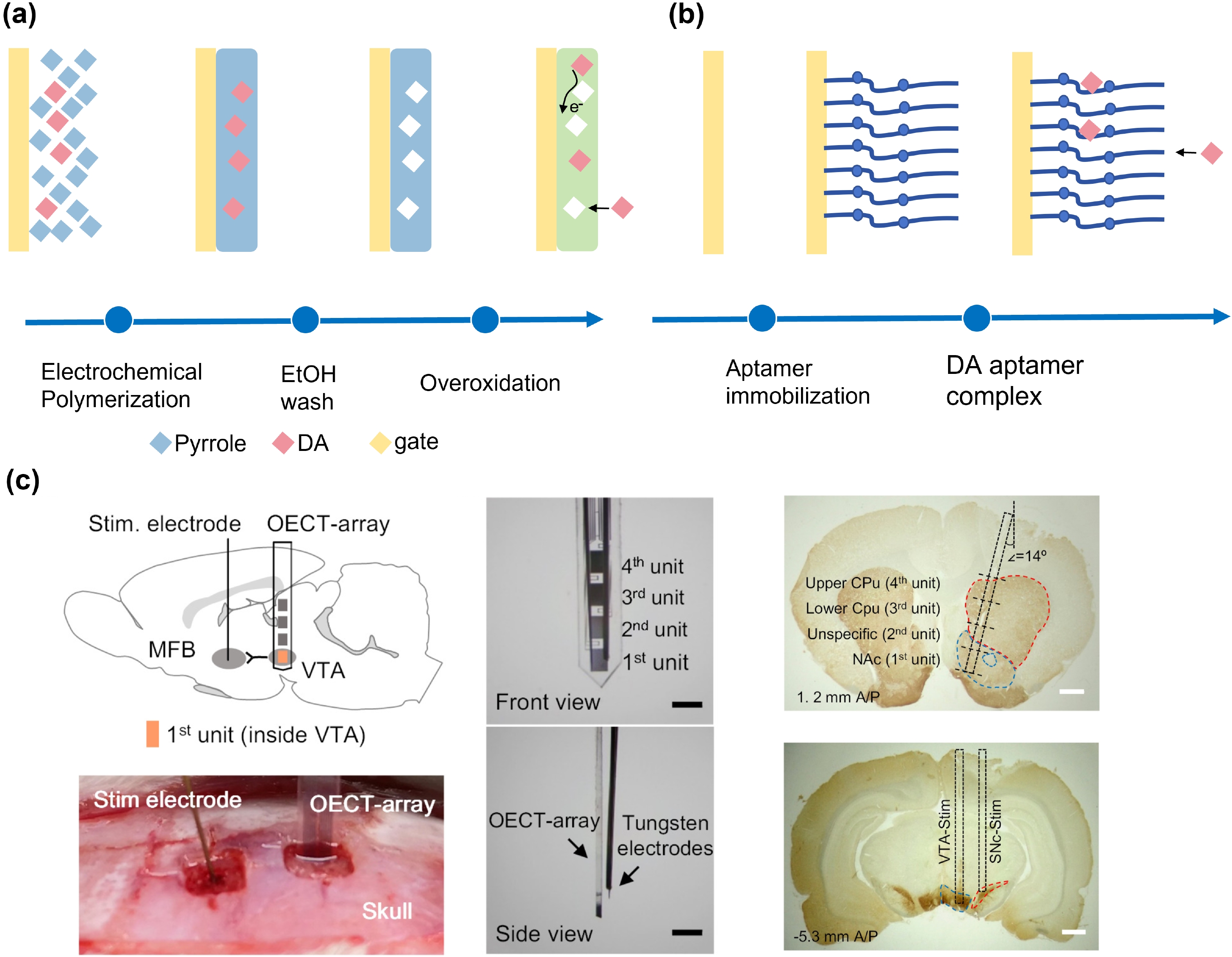

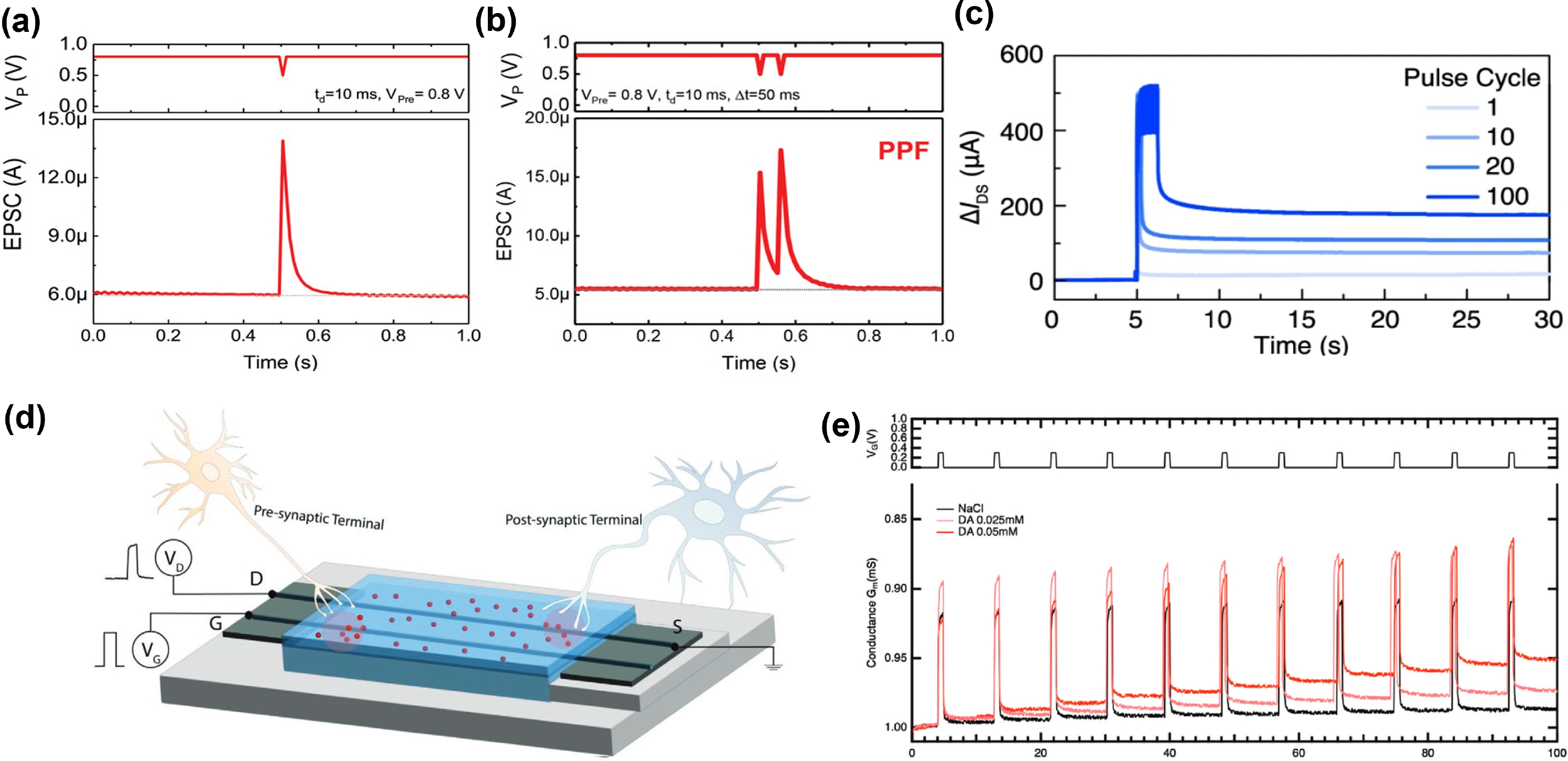

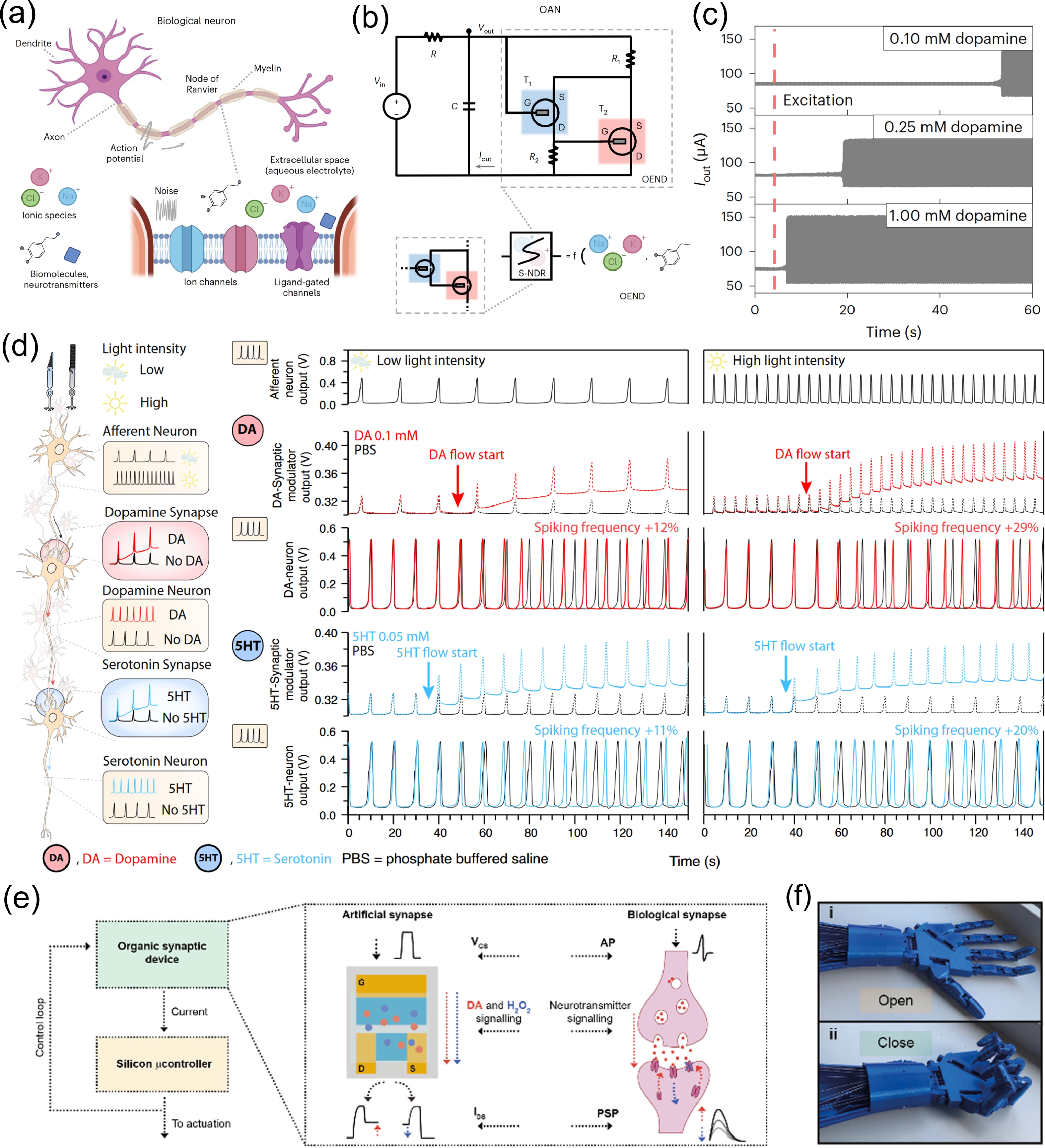

Organic electrochemical transistors have emerged as a solution for artificial synapses that mimic the neural functions of the brain structure, holding great potentials to break the bottleneck of von Neumann architectures. However, current artificial synapses rely primarily on electrical signals, and little attention has been paid to the vital role of neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses. Dopamine is a key neurotransmitter associated with emotion regulation and cognitive processes that needs to be monitored in real time to advance the development of disease diagnostics and neuroscience. To provide insights into the development of artificial synapses with neurotransmitter involvement, this review proposes three steps towards future biomimic and bioinspired neuromorphic systems. We first summarize OECT-based dopamine detection devices, and then review advances in neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses and resultant advanced neuromorphic systems. Finally, by exploring the challenges and opportunities related to such neuromorphic systems, we provide a perspective on the future development of biomimetic and bioinspired neuromorphic systems. -

References

[1] Pereda A E. Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2014, 15, 250 doi: 10.1038/nrn3708[2] Smart T G, Paoletti P. Synaptic neurotransmitter-gated receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2012, 4, a009662 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009662[3] Wang T, Wang M, Wang J W, et al. A chemically mediated artificial neuron. Nat Electron, 2022, 5, 586 doi: 10.1038/s41928-022-00803-0[4] Hyman S E. Neurotransmitters. Curr Biol, 2005, 15, R154 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.037[5] Zeisel S H. A brief history of choline. Ann Nutr Metab, 2012, 61, 254 doi: 10.1159/000343120[6] Kelly R B. Storage and release of neurotransmitters. Cell, 1993, 72, 43 doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80027-3[7] Su Y, Bian S M, Sawan M. Real-time in vivo detection techniques for neurotransmitters: A review. Analyst, 2020, 145, 6193 doi: 10.1039/D0AN01175D[8] Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Demling J, et al. Neue wege in der depressionsbehandlung. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr, 2007, 75, 641 doi: 10.1055/s-2007-959181[9] Pan J X, Xia J J, Deng F L, et al. Diagnosis of major depressive disorder based on changes in multiple plasma neurotransmitters: A targeted metabolomics study. Transl Psychiatry, 2018, 8, 130 doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0183-x[10] Iversen S D, Iversen L L. Dopamine: 50 years in perspective. Trends Neurosci, 2007, 30, 188 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.002[11] Banerjee S, McCracken S, Hossain M F, et al. Electrochemical detection of neurotransmitters. Biosensors, 2020, 10, 101 doi: 10.3390/bios10080101[12] Keene S T, Lubrano C, Kazemzadeh S, et al. A biohybrid synapse with neurotransmitter-mediated plasticity. Nat Mater, 2020, 19, 969 doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0703-y[13] Krauhausen I, Griggs S, McCulloch I, et al. Bio-inspired multimodal learning with organic neuromorphic electronics for behavioral conditioning in robotics. Nat Commun, 2024, 15, 4765 doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48881-2[14] Bruno U, Rana D, Ausilio C, et al. An organic brain-inspired platform with neurotransmitter closed-loop control, actuation and reinforcement learning. Mater Horiz, 2024, 11, 2865 doi: 10.1039/D3MH02202A[15] Rivnay J, Inal S, Salleo A, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat Rev Mater, 2018, 3, 17086 doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.86[16] Ferro L M M, Merces L, de Camargo D H S, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors: Ultrahigh-gain organic electrochemical transistor chemosensors based on self-curled nanomembranes. Adv Mater, 2021, 33, 2170223 doi: 10.1002/adma.202170223[17] Khodagholy D, Rivnay J, Sessolo M, et al. High transconductance organic electrochemical transistors. Nat Commun, 2013, 4, 2133 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3133[18] Liu H, Song J J, Zhao Z Y, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors for biomarker detections. Adv Sci, 2024, 11, 2305347 doi: 10.1002/advs.202305347[19] Spanu A, Martines L, Bonfiglio A. Interfacing cells with organic transistors: A review of in vitro and in vivo applications. Lab Chip, 2021, 21, 795 doi: 10.1039/D0LC01007C[20] Uguz I, Ohayon D, Arslan V, et al. Flexible switch matrix addressable electrode arrays with organic electrochemical transistor and pn diode technology. Nat Commun, 2024, 15, 533 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44024-1[21] Nawaz A, Liu Q, Leong W L, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors for in vivo bioelectronics. Adv Mater, 2021, 33, 2170387 doi: 10.1002/adma.202170387[22] Marks A, Griggs S, Gasparini N, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors: An emerging technology for biosensing. Adv Mater Interfaces, 2022, 9, 2102039 doi: 10.1002/admi.202102039[23] Saleh A, Koklu A, Uguz I, et al. Bioelectronic interfaces of organic electrochemical transistors. Nat Rev Bioeng, 2024, 2, 559 doi: 10.1038/s44222-024-00180-7[24] Li N, Li Y, Cheng Z, et al. Bioadhesive polymer semiconductors and transistors for intimate biointerfaces. Science, 2023, 381, 686 doi: 10.1126/science.adg8758[25] Chouhdry H H, Lee D H, Bag A, et al. A flexible artificial chemosensory neuronal synapse based on chemoreceptive ionogel-gated electrochemical transistor. Nat Commun, 2023, 14, 821 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36480-6[26] Dai S L, Zhao Y W, Wang Y, et al. Recent advances in transistor-based artificial synapses. Adv Funct Mater, 2019, 29, 1903700 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201903700[27] Huh W, Lee D H, Lee C H. Memristors based on 2D materials as an artificial synapse for neuromorphic electronics. Adv Mater, 2020, 32, 2002092 doi: 10.1002/adma.202002092[28] Bhunia R, Boahen E K, Kim D J, et al. Neural-inspired artificial synapses based on low-voltage operated organic electrochemical transistors. J Mater Chem C, 2023, 11, 7485 doi: 10.1039/D3TC00752A[29] Han H, Yu H Y, Wei H H, et al. Recent progress in three-terminal artificial synapses: From device to system. Small, 2019, 15, 1900695 doi: 10.1002/smll.201900695[30] Gkoupidenis P, Zhang Y, Kleemann H, et al. Organic mixed conductors for bioinspired electronics. Nat Rev Mater, 2024, 9, 134 doi: 10.1038/s41578-023-00622-5[31] Tang X, Shen H, Zhao S Y, et al. Flexible brain–computer interfaces. Nat Electron, 2023, 6, 109 doi: 10.1038/s41928-022-00913-9[32] Bischak C G, Flagg L Q, Ginger D S. Ion exchange gels allow organic electrochemical transistor operation with hydrophobic polymers in aqueous solution. Adv Mater, 2020, 32, 2002610 doi: 10.1002/adma.202002610[33] He R X, Lv A F, Jiang X Y, et al. Organic electrochemical transistor based on hydrophobic polymer tuned by ionic gels. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2023, 62, e202304549 doi: 10.1002/anie.202304549[34] Bernards D A, Malliaras G G. Steady-state and transient behavior of organic electrochemical transistors. Adv Funct Mater, 2007, 17, 3538 doi: 10.1002/adfm.200601239[35] Liang Y Y, Figueroa-Miranda G, Tanner J A, et al. Highly sensitive detection of malaria biomarker through matching channel and gate capacitance of integrated organic electrochemical transistors. Biosens Bioelectron, 2023, 242, 115712 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2023.115712[36] Rivnay J, Leleux P, Ferro M, et al. High-performance transistors for bioelectronics through tuning of channel thickness. Sci Adv, 2015, 1, e1400251 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400251[37] Flagg L Q, Giridharagopal R, Guo J, et al. Anion-dependent doping and charge transport in organic electrochemical transistors. Chem Mater, 2018, 30, 5380 doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02220[38] Ohayon D, Druet V, Inal S. A guide for the characterization of organic electrochemical transistors and channel materials. Chem Soc Rev, 2023, 52, 1001 doi: 10.1039/D2CS00920J[39] Xi X, Wu D Q, Ji W, et al. Manipulating the sensitivity and selectivity of OECT-based biosensors via the surface engineering of carbon cloth gate electrodes. Adv Funct Mater, 2020, 30, 1905361 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201905361[40] Ma X, Chen H Q, Zhang P W, et al. OFET and OECT, two types of organic thin-film transistor used in glucose and DNA biosensors: A review. IEEE Sens J, 2022, 22, 11405 doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2022.3170405[41] Tang H, Lin P, Chan H L W, et al. Highly sensitive dopamine biosensors based on organic electrochemical transistors. Biosens Bioelectron, 2011, 26, 4559 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.05.025[42] Xie K, Wang N X, Lin X D, et al. Organic electrochemical transistor arrays for real-time mapping of evoked neurotransmitter release in vivo. eLife, 2020, 9, e50345 doi: 10.7554/eLife.50345[43] Zhang M, Liao C Z, Yao Y L, et al. High-performance dopamine sensors based on whole-graphene solution-gated transistors. Adv Funct Mater, 2014, 24, 978 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201302359[44] Tseng H S, Chen Y L, Zhang P Y, et al. Additive blending effects on PEDOT: PSS composite films for wearable organic electrochemical transistors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2024, 16, 13384 doi: 10.1021/acsami.3c14961[45] Li Y, Cui B B, Zhang S M, et al. Ion-selective organic electrochemical transistors: Recent progress and challenges. Small, 2022, 18, 2107413 doi: 10.1002/smll.202107413[46] Liu X X, Liu J W. Biosensors and sensors for dopamine detection. View, 2021, 2, 20200102 doi: 10.1002/VIW.20200102[47] Justino C I L, Rocha-Santos T A, Duarte A C, et al. Review of analytical figures of merit of sensors and biosensors in clinical applications. Trac Trends Anal Chem, 2010, 29, 1172 doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2010.07.008[48] Wang N X, Liu Y Z, Fu Y, et al. AC measurements using organic electrochemical transistors for accurate sensing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2018, 10, 25834 doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07668[49] ernards D A, Macaya D J, Nikolou M, et al. Enzymatic sensing with organic electrochemical transistors. J Mater Chem, 2008, 18, 116 doi: 10.1039/B713122D[50] Beitollahi H, Mohadesi A, Mahani S K, et al. Simultaneous determination of dopamine, uric acid, and tryptophan using an MWCNT modified carbon paste electrode by square wave voltammetry. Turk J Chem, 2012, 36(4), 526 doi: 10.3906/kim-1112-5[51] Kim D S, Kang E S, Baek S, et al. Electrochemical detection of dopamine using periodic cylindrical gold nanoelectrode arrays. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 14049 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32477-0[52] Estrela P, Paul D, Song Q F, et al. Label-free sub-picomolar protein detection with field-effect transistors. Anal Chem, 2010, 82, 3531 doi: 10.1021/ac902554v[53] Wightman R M, Jankowski J A, Kennedy R T, et al. Temporally resolved catecholamine spikes correspond to single vesicle release from individual chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1991, 88, 10754 doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10754[54] Álvarez-Martos I, Ferapontova E E. A DNA sequence obtained by replacement of the dopamine RNA aptamer bases is not an aptamer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2017, 489, 381 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.134[55] Yildirim A, Bayindir M. Turn-on fluorescent dopamine sensing based on in situ formation of visible light emitting polydopamine nanoparticles. Anal Chem, 2014, 86, 5508 doi: 10.1021/ac500771q[56] Zhang X L, Zhu Y G, Li X, et al. A simple, fast and low-cost turn-on fluorescence method for dopamine detection using in situ reaction. Anal Chim Acta, 2016, 944, 51 doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.09.023[57] Liang Y Y, Guo T, Zhou L, et al. Label-free split aptamer sensor for femtomolar detection of dopamine by means of flexible organic electrochemical transistors. Materials, 2020, 13, 2577 doi: 10.3390/ma13112577[58] Soliman I, Gunathilake C. Aptamer-enhanced organic electrochemical transistors for ultra-sensitive dopamine detection. Next Mater, 2024, 3, 100160 doi: 10.1016/j.nxmate.2024.100160[59] Bertana V, Scordo G, Parmeggiani M, et al. Rapid prototyping of 3D organic electrochemical transistors by composite photocurable resin. Sci Rep, 2020, 10, 13335 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70365-8[60] Liao C, Zhang M, Niu L, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors with graphene-modified gate electrodes for highly sensitive and selective dopamine sensors. J Mater Chem B, 2014, 2, 191 doi: 10.1039/C3TB21079K[61] Tang K, Turner C, Case L, et al. Organic electrochemical transistor with molecularly imprinted polymer-modified gate for the real-time selective detection of dopamine. ACS Appl Polym Mater, 2022, 4, 2337 doi: 10.1021/acsapm.1c01563[62] Diforti J F, Piccinini E, Allegretto J A, et al. Empowering bioelectronics with supramolecular nanoarchitectonics: PEDOT-based organic electrochemical transistors with tunable electronic properties. ACS Appl Electron Mater, 2024, 6, 1211 doi: 10.1021/acsaelm.3c01592[63] Chou J A, Chung C L, Ho P C, et al. Organic electrochemical transistors/SERS-active hybrid biosensors featuring gold nanoparticles immobilized on thiol-functionalized PEDOT films. Front Chem, 2019, 7, 281 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00281[64] Mariani F, Quast T, Andronescu C, et al. Needle-type organic electrochemical transistor for spatially resolved detection of dopamine. Mikrochim Acta, 2020, 187, 378 doi: 10.1007/s00604-020-04352-1[65] Wu X Y, Feng J Y, Deng J, et al. Fiber-shaped organic electrochemical transistors for biochemical detections with high sensitivity and stability. Sci China Chem, 2020, 63, 1281 doi: 10.1007/s11426-020-9779-1[66] Massetti M, Zhang S L, Harikesh P C, et al. Fully 3D-printed organic electrochemical transistors. NPJ Flex Electron, 2023, 7, 11 doi: 10.1038/s41528-023-00245-4[67] Qing X, Wang Y D, Zhang Y, et al. Wearable fiber-based organic electrochemical transistors as a platform for highly sensitive dopamine monitoring. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2019, 11, 13105 doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b00115[68] Gualandi I, Tonelli D, Mariani F, et al. Selective detection of dopamine with an all PEDOT: PSS Organic Electrochemical Transistor. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 35419 doi: 10.1038/srep35419[69] BelBruno J J. Molecularly imprinted polymers. Chem Rev, 2019, 119, 94 doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00171[70] Zaidi S A. Development of molecular imprinted polymers based strategies for the determination of Dopamine. Sens Actuat B Chem, 2018, 265, 488 doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.03.076[71] Sinha K, Das Mukhopadhyay C. Quantitative detection of neurotransmitter using aptamer: From diagnosis to therapeutics. J Biosci, 2020, 45, 44 doi: 10.1007/s12038-020-0017-x[72] Sun H G, Zu Y L. A highlight of recent advances in aptamer technology and its application. Molecules, 2015, 20, 11959 doi: 10.3390/molecules200711959[73] Walsh R, DeRosa M C. Retention of function in the DNA homolog of the RNA dopamine aptamer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2009, 388, 732 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.084[74] Nakatsuka N, Yang K A, Abendroth J M, et al. Aptamer-field-effect transistors overcome Debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science, 2018, 362, 319 doi: 10.1126/science.aao6750[75] Li W Q, Jin J, Xiong T Y, et al. Fast-scanning potential-gated organic electrochemical transistors for highly sensitive sensing of dopamine in living rat brain. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2022, 61, e202204134 doi: 10.1002/anie.202204134[76] Ling H F, Wang N X, Yang A N, et al. Dynamically reconfigurable short-term synapse with millivolt stimulus resolution based on organic electrochemical transistors. Adv Mater Technol, 2019, 4, 1900471 doi: 10.1002/admt.201900471[77] Ji X D, Paulsen B D, Chik G K K, et al. Mimicking associative learning using an ion-trapping non-volatile synaptic organic electrochemical transistor. Nat Commun, 2021, 12, 2480 doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22680-5[78] Alarcon-Espejo P, Sarabia-Riquelme R, Matrone G M, et al. High-hole-mobility fiber organic electrochemical transistors for next-generation adaptive neuromorphic bio-hybrid technologies. Adv Mater, 2024, 36, 2305371 doi: 10.1002/adma.202305371[79] Kim K N, Sung M J, Park H L, et al. Organic synaptic transistors for bio-hybrid neuromorphic electronics. Adv Electron Mater, 2022, 8, 2100935 doi: 10.1002/aelm.202100935[80] Liu G C, Li Q Y, Shi W, et al. Ultralow-power and multisensory artificial synapse based on electrolyte-gated vertical organic transistors. Adv Funct Mater, 2022, 32, 2200959 doi: 10.1002/adfm.202200959[81] Wang S Y, Wu M H, Liu W C, et al. Dopamine detection and integration in neuromorphic devices for applications in artificial intelligence. Device, 2024, 2, 100284 doi: 10.1016/j.device.2024.100284[82] Luo S, Shao L, Ji D Z, et al. Highly bionic neurotransmitter-communicated neurons following integrate-and-fire dynamics. Nano Lett, 2023, 23, 4974 doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00799[83] Xu Q, Chen J W, Li Y, et al. Fully printed dual-gate organic electrochemical synaptic transistor with neurotransmitter-mediated plasticity. IEEE Electron Device Lett, 2024, 45, 104 doi: 10.1109/LED.2023.3335970[84] Matrone G M, Bruno U, Forró C, et al. Electrical and optical modulation of a PEDOT: PSS-based electrochemical transistor for multiple neurotransmitter-mediated artificial synapses. Adv Mater Technol, 2023, 8, 2201911 doi: 10.1002/admt.202201911[85] Sarkar T, Lieberth K, Pavlou A, et al. An organic artificial spiking neuron for in situ neuromorphic sensing and biointerfacing. Nat Electron, 2022, 5, 774 doi: 10.1038/s41928-022-00859-y[86] Matrone G M, van Doremaele E R W, Surendran A, et al. A modular organic neuromorphic spiking circuit for retina-inspired sensory coding and neurotransmitter-mediated neural pathways. Nat Commun, 2024, 15, 2868 doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47226-3[87] Marion J S, Gupta N, Cheung H, et al. Thermally drawn highly conductive fibers with controlled elasticity. Adv Mater, 2022, 34, 2201081 doi: 10.1002/adma.202201081[88] Yan W, Noel G, Loke G, et al. Single fibre enables acoustic fabrics via nanometre-scale vibrations. Nature, 2022, 603, 616 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04476-9[89] Santhanam G, Ryu S I, Yu B M, et al. A high-performance brain-computer interface. Nature, 2006, 442, 195 doi: 10.1038/nature04968[90] Campana A, Cramer T, Simon D T, et al. Electrocardiographic recording with conformable organic electrochemical transistor fabricated on resorbable bioscaffold. Adv Mater, 2014, 26, 3874 doi: 10.1002/adma.201400263[91] Braendlein M, Lonjaret T, Leleux P, et al. Voltage amplifier based on organic electrochemical transistor. Adv Sci, 2017, 4, 1600247 doi: 10.1002/advs.201600247[92] Harikesh P C, Yang C Y, Wu H Y, et al. Ion-tunable antiambipolarity in mixed ion-electron conducting polymers enables biorealistic organic electrochemical neurons. Nat Mater, 2023, 22, 242 doi: 10.1038/s41563-022-01450-8[93] Tian H H, Hu Z Y, Xu J, et al. The molecular pathophysiology of depression and the new therapeutics. MedComm, 2022, 3, e156 doi: 10.1002/mco2.156[94] Bian X, Zhou N, Zhao Y, et al. Identification of proline, 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate and glutamic acid as biomarkers of depression reflecting brain metabolism using carboxylomics, a new metabolomics method. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2022, 77, 196 doi: 10.1111/pcn.13517[95] Lee Y, Liu Y X, Seo D G, et al. A low-power stretchable neuromorphic nerve with proprioceptive feedback. Nat Biomed Eng, 2023, 7, 511 doi: 10.1038/s41551-022-00918-x -

Proportional views

Miao Cheng received his bachelor's degree at Lanzhou University. Now he is a PhD student at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing under the supervision of Prof. Mengmeng Li. His research interests include organic electrochemical transistor and optoelectronic devices.

Miao Cheng received his bachelor's degree at Lanzhou University. Now he is a PhD student at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing under the supervision of Prof. Mengmeng Li. His research interests include organic electrochemical transistor and optoelectronic devices. Yifan Xie received his bachelor's degree at Beijing Normal University. Now he is a PhD student at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing, under the supervision of Prof. Mengmeng Li. His research interests include organic semiconducting transistors and flexible electronics.

Yifan Xie received his bachelor's degree at Beijing Normal University. Now he is a PhD student at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing, under the supervision of Prof. Mengmeng Li. His research interests include organic semiconducting transistors and flexible electronics. Mengmeng Li is currently working as a full professor at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing. He obtained his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Germany. Afterward, he joined Eindhoven University of Technology and the Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research as a senior researcher for his independent research, where he was awarded the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (European Commission) and a Talent Programme Veni grant (NWO), respectively. His current research interests include organic thin-film transistors, flexible electronics and new physics on the nanoscale.

Mengmeng Li is currently working as a full professor at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing. He obtained his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Germany. Afterward, he joined Eindhoven University of Technology and the Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research as a senior researcher for his independent research, where he was awarded the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (European Commission) and a Talent Programme Veni grant (NWO), respectively. His current research interests include organic thin-film transistors, flexible electronics and new physics on the nanoscale. Ling Li is currently working as a deputy director and professor at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing. He obtained bachelor degree in University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, master degree in Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China and PhD degree in Vienna University of Technology, Austria. He later worked as a research professor at Kyung Hee University in South Korea. As the project leader and technical backbone, he has participated in more than ten national, provincial and ministerial level scientific research projects, including 863 Program projects, National Key Research and Development Program, National Natural Science Foundation of China Distinguished Youth Program, CAS Pioneer Special Projects, etc. In addition, he has published more than 100 papers in Nature Communications, Nano Letters, and top microelectronics conferences such as IEDM and VLSI, and applied for more than 50 invention patents.

Ling Li is currently working as a deputy director and professor at the Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing. He obtained bachelor degree in University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, master degree in Institute of Microelectronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China and PhD degree in Vienna University of Technology, Austria. He later worked as a research professor at Kyung Hee University in South Korea. As the project leader and technical backbone, he has participated in more than ten national, provincial and ministerial level scientific research projects, including 863 Program projects, National Key Research and Development Program, National Natural Science Foundation of China Distinguished Youth Program, CAS Pioneer Special Projects, etc. In addition, he has published more than 100 papers in Nature Communications, Nano Letters, and top microelectronics conferences such as IEDM and VLSI, and applied for more than 50 invention patents.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: